Standing inside a Hindu temple in Chennai, India, I watch horrified as a two-year-old girl with long, dark tresses has her head shaved.

She screams as the clippers buzz around her ears and her hair tumbles to the floor.

She is clearly terrified and no doubt has little comprehension of what is happening to her.

Beside her, her mother is having her head shaved, too.

This is a religious sacrifice: the shaving represents a last-ditch plea to a higher power to save their home from being repossessed.

But to me, it appears to be the ultimate in exploitation.

Their hair is casually tossed into a bin, but it will never actually be thrown away.

Though they do not know it, soon their pigtails and plaits will be sold to hair dealers and then shipped on to the salons of Western Europe.

As I watch the lady and her daughter shuffle out, hopeful that this huge sacrifice will make some tangible difference to their lives, I make a promise to myself that I will never wear hair extensions again.

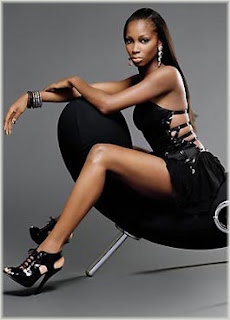

My hair has always been important to me.

As a schoolgirl, I used to get up at 5am to ensure I had enough time to do my hair before school.

Although for a black woman I would be described as having ‘good’ hair – because it is long and straight – naturally, it is not luxurious, thick or sleek enough to meet the demands of the endless photo shoots and concerts I am involved in for my career.

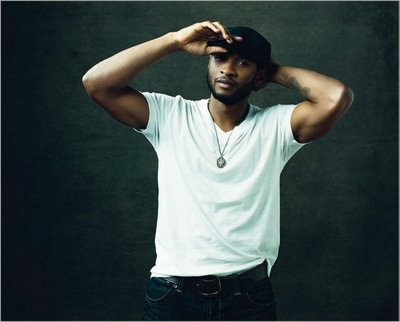

That’s why, in many of the photographs you see of me, I am wearing hair extensions.

For me, putting in my hair extensions feels like a confidence booster, like a man putting on a smart suit.

I wear them to bring out the best in me and to transform myself from busy mum of two into my alter ego, Jamelia the pop star.

And I’m not alone.

All over Britain, girls are clipping, glueing and sewing hair into their heads.

Recent figures show that British women spend a staggering £65 million a year on hair extensions.

As a nation, we now spend five times more on lengthening our hair than we did four years ago.

Yet most of us give very little consideration to the origin of our hair extensions.

Indeed, until I worked on this BBC investigation, I’m ashamed to admit I’d never once stopped to consider where the human hair I had pinned or sewn into my head had come from.

I was so ignorant about the products I was using that I can’t even say how much they were costing me every month or every year.

Then I heard from a friend, earlier this year, that the hair used in the extensions could be taken from corpses. I was horrified.

How did I know I wasn’t wearing a dead person’s hair?

And if I was, had they agreed to that before they passed away, or had they simply had it shaved off in a mortuary without their family’s knowledge?

And if the hair wasn’t taken from the dead, who were this army of women and girls from whom it was taken?

I realised for the first time that there might be a very real human cost to the beauty fad which allowed me to feel more confident on stage.

I wanted to know who on earth was chopping off other people’s hair in the name of our Western vanity, and whose hair I have actually been wearing?

My journey to find out took me via some of London’s most upmarket hair salons and into the heart of rural Russia and India.

What I discovered was truly shocking and distressing.

Did you know, for instance, that in Russia, girls as young as 13 are cutting off their hair to sell for just a few pounds?

This is despite the fact that in the UK, a full head of extensions of the best quality European hair would set you back £2,000.

There is a staggering profit to be made from this trade, and you can bet that none if it is passed back to the girls at the beginning of the chain.

I start my journey by visiting Russia with Tatiana Karelina, a Russian hair-extension expert living in London.

She does 1,000 sets of hair every year for private clients, and is known for providing top-quality soft and fine hair.

She frequently travels to her homeland to source top-quality hair straight from dealers.

We head to a remote rural area three hours from Moscow, where we meet Alexander, a hair dealer.

He tells us his hair is provided to him from collectors, who go around small villages and towns persuading women and girls to sell their hair.

I have a lot of questions for Alexander. I ask him if he knows whether the girls whose hair he sells are being treated fairly.

I ask him if he ever gets hair from dead people. He is cagey and evasive.

He says that he knows the hair doesn’t come from the dead, but he won’t elaborate further.

But when I press him, he finally confesses that he doesn’t know exactly where the hair he is buying comes from.

And by way of illustrating that, the girls who sell hair are treated fairly, he simply states that they know the worth of their hair and wouldn’t sell it unless they were getting paid well.

And by way of illustrating that, the girls who sell hair are treated fairly, he simply states that they know the worth of their hair and wouldn’t sell it unless they were getting paid well.

I leave the meeting feeling deeply uncomfortable.

This man is not sure that the hair he sells is not from dead people, and I’m starting to be convinced that someone is being exploited along the way.

Let’s face it – the rich girls tottering around Red Square in designer heels and carrying Louis Vuitton bags do not need to sell their hair.

Next, Tatiana takes me to her home town of Kashin, another rural area, where we meet a 13-year-old girl, also called Tatiana, who has long hair which reaches her backside.

She tells us she wishes to sell her hair because she has been told she will be paid for it.

To my mind, it’s a travesty – this girl’s hair is gorgeous and she seems too young to really know for sure whether she’s making the right decision.

Usually, this full head of luxurious hair would have cost just £20. Today, perhaps because I am watching, Tatiana pays the girl £100.

It’s the equivalent of most people’s monthly wages here, and the girl is over the moon.

But I feel incredibly uncomfortable about the entire process – there’s something so deeply personal about your hair: it should be every woman’s pride and joy.

What British teenager would ever dream of doing the same?

For the next stage of my investigation, I travel to Chennai, one of the biggest cities in India.

As part of the documentary, I have had some of the hair I wear in my extensions scientifically analysed. The results suggest it comes from this region of India.

In Indian culture, a woman’s hair is her beauty, and the longer your hair, the better your marriage prospects are.

Why then, with such value placed on hair, would anyone even consider selling it?

Yet, incredibly, there are so many women prepared to chop off their hair here that factories have sprung up to process it.

On my visit, I go to see one where the workers sort through, shampoo, brush and blow dry the shorn hair of more than 200,000 women a year. To me, it’s a macabre thought.

So why exactly do these women do it?

Well, as I have mentioned already, there are the many Indian women who shave their hair voluntarily at Hindu temples as a kind of religious sacrifice.

And although some of these women know the hair will be sold, most don’t.

One woman I come across is having her head shaved to give thanks for the fact her child has recovered from a life-threatening illness; another to save her property from repossession.

They clearly believe this is the best way to show their faith and gratitude, and I’m told that millions of pounds raised from selling their hair is spent on the homeless and maintaining the temples.

And yet only a quarter of Indian hair sold on the international market comes from Hindu temples, which means that most of it is coming from women who are simply trying to make a little money.

I also travel to an impoverished village to see how poor-quality hair – the sort that sells on our market stalls in extensions for £5 – is collected.

There, I witness men and women working the rubbish dumps, actually searching for and collecting hair that has been pulled out of hair brushes.

Quite simply, this is their family business. It is, they tell me, a job their fathers and grandfathers have done before them.

It might seem disgusting, but it’s the only income they have.

It is a pitiful existence, and it is fuelled by the demand from Britain and other countries.

What I saw in Russia and India certainly set me thinking, and since I returned I haven’t used hair extensions once, not even when performing at the recent Nelson Mandela tribute concert in Hyde Park.

That was the sort of event at which previously I would never have stepped on stage without them.

But what I have unearthed has profoundly changed my attitude about extensions.

Now, to me, a packet of hair extensions has a face – whether that is a Russian teenager, a woman in India who is shaving her head as a sacrifice or a two-year-old girl in tears because she doesn’t understand what’s happening to her.

I believe that I – and all the other women who use them – should be more responsible about the extensions we buy.

As consumers, we need to make sure that the hair we use is ethical, and has been given with consent.

We need to know that the people it has come from have been treated fairly.

Just as we have fair trade stamps for food, why shouldn’t we have the same thing for hair extensions?

And as the women who drive the market in hair extensions, we also have a moral responsibility to the women who have cut off their hair or shaved their heads for our benefit.

Their hair may be helping to make us more attractive, but thanks to their sacrifice many of them must now be anything but.